Welcome back.

In the first part of this article, we explored solvency management within operational treasuries. As a quick reminder, solvency management—keeping an organisation solvent for as long as possible—is a treasury’s primary duty. In this second part, we’ll focus on strategic solvency management, the level most valuable and of interest to non-treasurers.

To stay consistent, please imagine once again that you are a key decision-maker at Acme Manufacturing Corporation, a company with a multi-billion-dollar turnover, aiming to establish a value-adding treasury to keep the company solvent through changing business circumstances and as profitable as possible.

You’ve already assessed the operational treasury options:

- Basic treasury: This is not a standalone function but a daily activity of payments, receipts, funding, and investments managed by the accounting department (daily cash management). You quickly ruled this option out.

- Control-oriented treasury: Here, the treasury handles liquidity (financing and investments under one year) and daily cash management.

A control-oriented treasury might be suitable if your organisation’s context allows only minimal change for now or has a limited openness to delegated financial management. But, for now, let’s assume that conditions favour a more strategic approach. Suppose management and key stakeholders are ready for change and willing to invest in a treasury that not only ensures solvency in a crisis but also generates profit under regular circumstances—much like Amazon Web Services does for Amazon in IT.

With support for innovation in place, you decide it’s time to learn more about strategic treasuries and, most of all, about strategic solvency management.

Strategic solvency management: Financing optimisation and value-chain financing

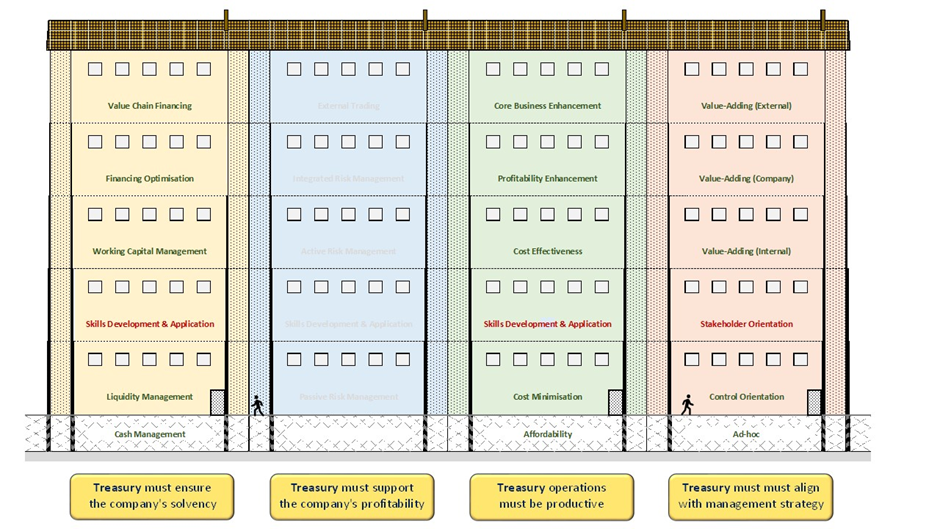

From the last article: “The six levels of solvency management sophistication are:

- Cash management

- Liquidity management

- [New] Skills development and application

- Working capital management

- Financing optimisation

- Value-chain financing”

The strategic levels are “Financing Optimisation” and “Value-Chain Financing”.

These two levels are similar and related. Both have reached levels where the organisation can be confident the company will not become insolvent during ordinary and, as far as possible, in extraordinary times. Both prove their worth daily by showing management that their capabilities – those needed to handle a crisis – are strong enough that they produce a profit during other times.

The difference between the two is in focus:

‘Financing Optimisation’ level treasuries provide value-adding financing (and associated investments) to the organisation’s internal functions, such as sales and procurement, so that they can deliver the organisation’s products and funding in one integrated offering to customers and suppliers (Cisco Capital, Tesla Financing).

‘Value-chain financing’ level treasuries do so directly with external counterparties, for example, equipment financing functions where the financing arm often finances equipment from competitors and other manufacturers in addition to their own (Caterpillar Financial Services, Siemens Financial Services).

A ‘value-chain financing’ treasury is a separate line of business that includes a ‘financing-optimisation’ level treasury within it and has, in addition, an externally-facing salesforce and other departments needed by the function to operate standalone.

Benefits of strategic solvency management

The benefits of a strategic approach to solvency management are far beyond what operational treasuries offer.

Beneficiaries

Many non-treasury departments can become more effective by hiring skilled treasury professionals and putting them in a well-structured, controlled treasury environment. These include:

- Sales

- Procurement

- Mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

- Project financing

- Corporate finance

- HR (employee benefits)

- Tax

And potentially more. All at the same time. For these levels of treasury function, it doesn’t matter which internal departments or external parties need what. If it’s related to cash flows and their associated implications, it’s what strategic treasuries know about and manage. It’s their bread and butter.

Of course, these treasury functions must do more than receive requests passively and process them mindlessly. As strategic partners, they must understand the details of these requests and provide their customers with insights into potential consequences such as unforeseen costs, uncovered risks and missed opportunities.

Benefits

A strategic solvency-focused treasury provides departments with the following advantages:

- A range of financing options, including equity and debt, as well as options for investments when there’s a cash surplus. But more significantly:

- Flexibility, which can include choices on:

- Currencies

- Pricing

- Payment and repayment schedules

- Options to integrate financing into the organisation’s core offerings or keep it separate

- Fixed pricing periods

- Mid-contract adjustments

- Pre-arranged terms for contract rollovers and extensions

- Combinations of all of the above

In other words, the ability to tailor cashflows associated with offerings to whatever the client counterparties want.

Examples of flexibility in action

Imagine, for instance, that the sales team wants to offer a client financing to purchase expensive machinery. To compete effectively, they might want to keep the price unchanged while the client considers the offer. They might also like to provide flexible payment schedules or adapt to a custom payment plan asked for by the client. The more options treasury can offer, the more likely sales will win the deal.

Another example could be when treasury works alongside procurement to negotiate with suppliers where the relationship is vital, but the purchasing power is on the suppliers’ side. Treasury can support procurement in exploring options with the suppliers, such as paying them in their preferred currencies or including interim stage payments. Treasury can support procurement to maintain and even deepen these strategic business relationships.

Of course, sales and procurement could do this without treasury’s help. But they are not financial market experts. The risks of them getting it wrong, creating losses and harming their key relationships would be more likely.

Such flexibility is invaluable in dealings with external customers, suppliers, employees, and sometimes even tax authorities. Even though market conditions fluctuate and rates vary constantly, non-treasury functions can give their counterparts whatever financial certainty they desire. Naturally, there’s a cost associated with this flexibility. However, organisations typically charge a smaller uplift for financing that’s directly tied to their core business compared to third parties like banks.

Acme Manufacturing can do the same.

Associated costs and infrastructure

OK, fine, the benefits are substantial – What about the costs?

- The experts aren’t cheap.

- They need roles where they are empowered, or they won’t stay.

- They need costly specialist equipment.

- The managers of this sophisticated function must understand both treasury specialisms and the broader business environment. People with this combined expertise are scarce and, therefore, also expensive.

- Flexibility and a dynamic environment require real-time controls. These can only be delivered effectively with more and better systems and personnel, adding yet more costs.

When factoring in cover for absences, staff turnover, handovers, and project needs, the scope and costs of a strategic treasury are substantial. Acme must approach this intricate treasury function’s structuring, implementation, management and ongoing support with great care if it is to succeed.

Organisational Structure

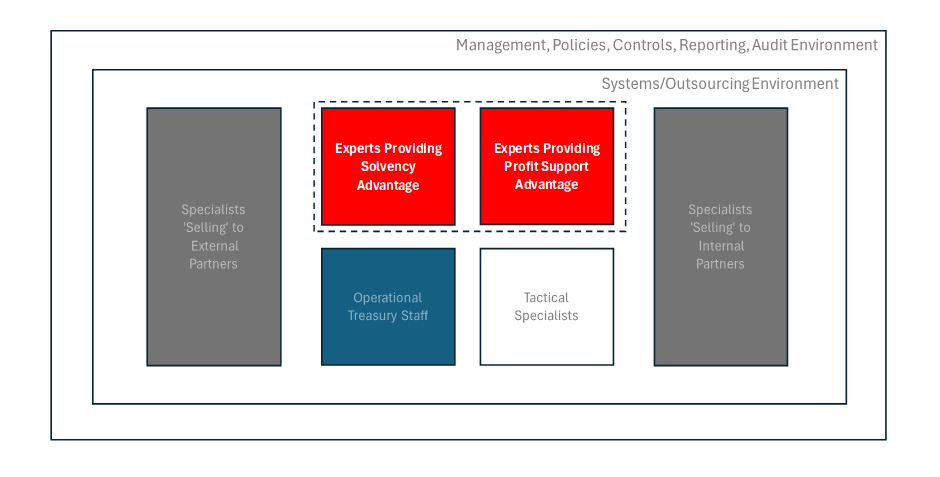

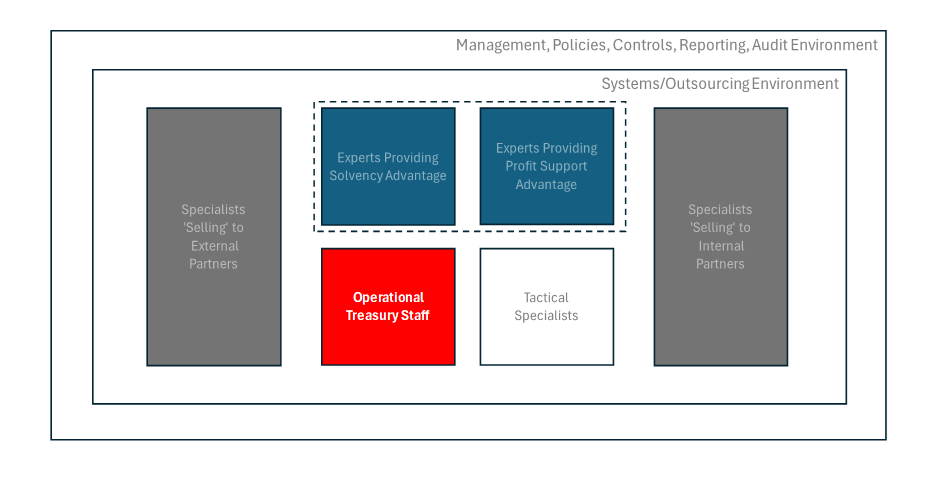

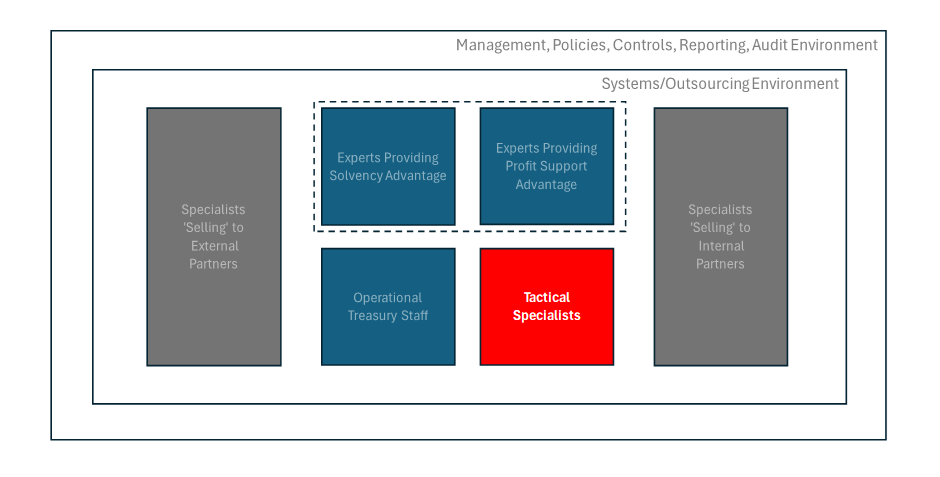

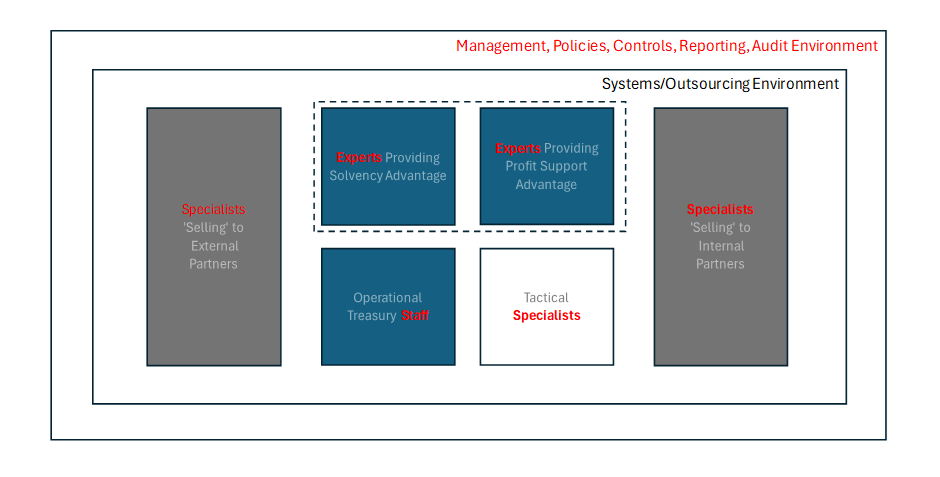

A sound organisational structure is vital to a strategic treasury’s stability, health and longevity. Non-treasurers need to understand the internal structures of these functions to see if they will be suitable long-term partners for them.

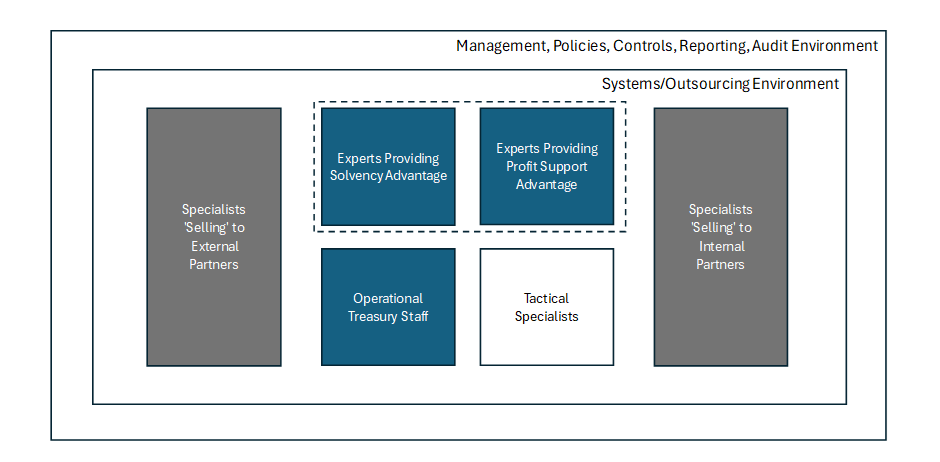

Base components

Given the complexity and similarity to a bank’s needs, it’s not surprising that successful strategic treasuries adopt organisational structures similar to those in banks. Key roles within a strategic treasury include:

Salespeople-Equivalents: These specialists liaise with internal and external clients. Their role is to understand clients’ needs, advocate for their interests within the treasury function, and translate their requirements into words other treasury colleagues understand.

Examples:

- Treasury Funding Specialists: These provide tailored financing from the central treasury to operating units, allowing them to extend competitive financing options to clients. Personal example: At IBM, we initially provided financing to leasing functions in forms that suited treasury, letting their profits be at risk due to fluctuating interest rates. When we became more sophisticated, we improved our offering to them. Subsidiaries would share the cashflows they expected to receive from customers with us, and we would offer to buy them at their market value, leaving them with no financial risk. Periodically, we’d repeat the process to ensure we were always aligned. This change stabilised their profit margins. In addition, for more significant deals, they reached out to us for special terms that would give them an edge over competitors. This change was immediately well received.

- M&A Treasury Specialists: These are experts in financial due diligence and financing and risk management for mergers and acquisitions. They coordinate with the target company, advisors and banks to secure funding, manage risks, and integrate penalties or benefits if reality differs from expectations. These experts play a crucial role in minimising potential losses by proactively preparing for financial uncertainties.

Traders-Equivalents: These market specialists work directly with banks to meet solvency (financing and investment) and profit-support (risk management) needs.

Financial risks vary, and the costs of managing them differ significantly. Skilled traders know how to borrow strategically, spreading refinancing over time and among various lenders to minimise the likelihood of critical funding facilities being unavailable during a crisis. All at the best cost possible. They build strong relationships with the banks, aiming to get favourable terms and to create allies within those banks who will help them should financial troubles arise.

Note that unlike the ‘salespeople-equivalents’, these experts are the customers when dealing with banks, not providers. The relationship dynamics and negotiation skills required are very different.

Middle Office Personnel: These control-oriented staff review all transactions from ‘sales’ and ‘trading,’ checking that there are no mistakes or frauds. They confirm that all activities comply with management-approved policies. Sales and trading’s verbal agreements only become binding contractual obligations once they have carried out their checks.

While this function may sound new, it’s actually a variant of the control-oriented treasury we looked at before—only here, one that acts in real-time and on a larger number of transactions.

Back Office Personnel: After transactions are confirmed, these operational groups handle cash payments, record accounting entries, and complete bank reconciliations, tasks even a basic treasury carries out, although, again, faster and with more payments. And with extra refinements, usually.

In Figures II and V, what a bank might call the Middle and Back Offices is what we’ll refer to as the Operational Treasury. This Operational Treasury—comprising both control-oriented and basic treasury functions—now operates as a sub-function within the broader strategic treasury.

Specialist roles

In addition to core roles, strategic treasuries also rely on other specialists. Specialists such as internal controllers, accountants, legal advisors, IT professionals, data scientists, project managers, general managers, or others, depending on the treasury’s activities. Large strategic treasuries may even have dedicated HR and procurement specialists, though these typically operate outside of treasury. Tax professionals can be in treasury or the main organisation. It depends on the organisation.

These specialists also appear in tactical treasuries; we’ll explore this aspect in more detail soon. For now, the primary distinction between specialists in tactical and strategic treasuries is scale: in tactical treasuries, there might only be one or two individuals per speciality, whereas strategic treasuries often have entire teams dedicated to these functions.

Geographic and timezone components

A noteworthy specialist role is that of the Regional or Country Treasury Centre Manager.

When an organisation has significant overseas operations in complex markets or different time zones, relying solely on a head-office treasury is impractical. A head office-only treasury will struggle to understand local requirements, navigate different environments, and respond quickly. In these cases, strategic treasuries often establish the same or many sub-functions outlined in Figure 2 within a region or country. An experienced manager, well-versed in the specific country or regional landscape, oversees these sub-functions and reports directly to the Organisation or Group Treasurer.

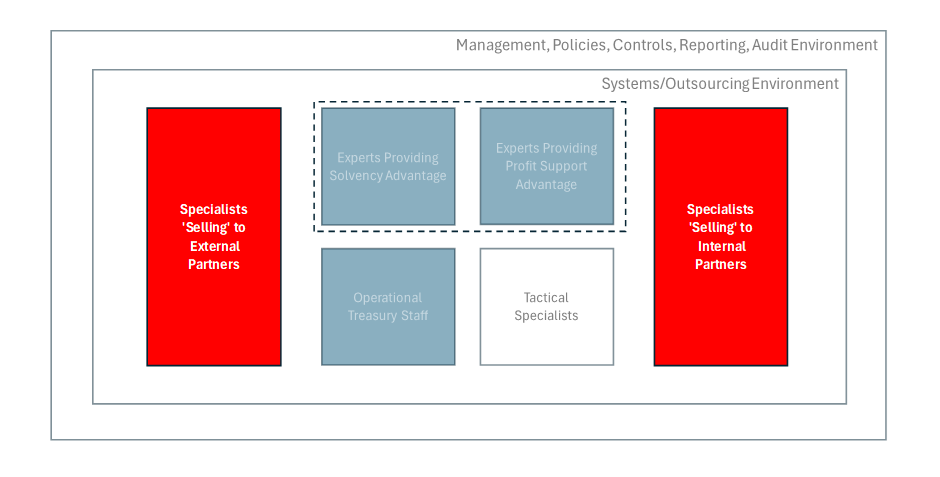

Bringing it all together – Drivers behind the organisational structure

Two key aspects drive organisational structure: 1) How different people work individually, together and in groups, and 2) how to manage diverse groups for optimal results. A correctly structured treasury takes the pressure off the individuals and lets group dynamics do the hard work. Getting this right makes the function robust.

- Optimal results: Role specialisation for clarity and efficiency Experts and specialists working with customers need to be client-oriented and adaptable. Those who work with suppliers (banks and other providers) must be partnership-oriented and collaborative. Operational staff must be process-oriented and precise, aiming for efficiency through standardisation. These are different outlooks, often at odds with each other. Research has shown that individuals and groups perform sub-optimally when there is inner conflict (Cognitive Dissonance). Real life confirms it. By creating sub-groups with simple and homogeneous outlooks, each sub-group gains clarity of purpose and a common sub-culture adaptable to ever-changing contexts. This arrangement frees individuals from the unrealistic expectation of excelling in all ways, all the time, every day.

- Optimal controls: Built-in safeguards and controls Policies, job descriptions, systems, and processes—like those discussed with control-oriented treasuries—are designed to minimise the risk of large-scale fraud and errors. However, none of these can prevent collusion by people working with each other to invalidate the built-in safeguards. Separating people into distinct sub-functions creates natural psychological barriers. In-group and out-group dynamics, driven by unconscious biases and behaviours, make individuals less likely to be intimate enough to conspire across groups. The barriers reduce the chance of collusion. Psychological barriers work well. The bigger the treasury and the greater the risk, the more psychological barriers there will be (IBM, Dow Chemical).

- Effective management: Checks and balances and managerial focus The finely balanced tensions created by having differently targeted sub-functions result in natural checks and balances that keep the activities of each sub-function controlled and productive – with less need for involvement by management. This organisational structure means managers don’t have to be experts at everything and don’t need to monitor all transactions at all times. It allows them to focus on setting objectives, handling exceptions, managing personnel and dealing with external stakeholders. Like their team members, they also do not need to be superhuman and excel at everything, at all times, every day.

The benefit of this organisational structure is that it enables a treasury operation to be effective and controlled despite the size of its operations and the need to operate in real-time. However, maintaining productivity and flexibility in real-time still requires efficient and clear communication across the sub-functions. Therefore, management must balance reducing operational risk and organisational effectiveness. The optimal structure will depend on the activities, target clients, required staffing and infrastructure involved.

Relevance to non-treasurers

Why do non-treasurers need this level of detail?

For two crucial reasons: Non-treasurers must understand that:

- Large organisations’ core activities produce significant, hard-to-predict cash flows and financial risks. Actively managing them controls them better and benefits the organisation more than passive management. With the right structure and skilled people, these functions do not endanger the organisation’s safety. Instead, they allow intelligent management of cashflow uncertainty and market fluctuations that the underlying organisation generates anyway. Non-treasurers in organisations should advocate for establishing strategic treasuries, knowing these can be set up to deliver value to their functions while remaining efficient and controlled.

- Not all treasuries described as strategic by treasurers and CFOs are structured to an acceptable standard. Non-treasurers – including CFOs – should be aware of and address this openly. Some treasuries may claim a “seat at the table,” but if they lack proper separation of duties and controls, as exemplified by the structure in Figure 2, or proper effectiveness, those are red flags. A treasury organised around the (unstated) assumption that individuals can handle any scenario or role at any time, at a moment’s notice, will sooner or later fail. This has happened before. ABB lost $73 million in Korea due to inadequate separation of duties. Siemens lost €38 million due to weak controls over its dealers.

Strategic treasuries don’t have a right to exist. They have to earn that right.

CFOs, boards, and risk committees must demand and ensure robust controls are in place. Sales, procurement, and other functions that rely on treasury support to provide their key business partners with services have a right to expect a well-structured function – robust and effective. Asking treasury to explain its role, processes, and controls – as part of due diligence on a key business partner – is sensible, good business practice.

Additional notes

Solvency optimisation and risk management (strategic profitability support)

You will have noticed that this article includes a lot about risk despite being about solvency optimisation (financing, investment and the like). Your observation is correct. The more sophisticated the borrowing or lending, the more need there is to manage risks. For example, a US company that usually borrows dollars in the US might want to borrow yen in Japan to reduce the likelihood of both borrowings being repayable simultaneously. They can do this but must, as a result, also manage the currency risk this increase in sophistication creates. Sophisticated solvency managing treasuries must also have sophisticated risk management. We’ll talk more about this in a later article.

Risk-aversion and strategic treasury benefits

The risks and controls mentioned above may seem daunting. It’s natural to feel concerned about complexity in non-core parts of the business, especially in areas outside one’s expertise. Most people fear potential losses more than they value potential gains. But consider this: Cash forecasts from non-treasury functions will always contain some degree of error. “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future,” as Yogi Berra said. As financial markets are constantly moving, organisations that don’t have experts to manage their cashflows and risks dynamically are, even if it’s unstated, relying on luck. Don’t trust lines like “On balance, the gains and losses even themselves out.” Relying on luck when 80% of companies that go out of business do so because of insolvency is unwise.

If you agree that intelligent management is needed, note further that professionals who aren’t allowed to apply their skills will lose them. A less sophisticated treasury with non-experts might fail to develop – or can lose – adequate internal controls, increasing the risks of fraud and error. ABB’s loss in Korea hints at this: the fraud occurred after the company’s restructuring due to asbestos-related losses – a restructuring that included the downsizing of its strategic treasury. While we can’t be sure this contributed to the loss of effective controls, we can be sure that a well-structured, skilled treasury with the right balance of personnel is better equipped to manage solvency and risks than one without.

Adaptability and role integration

Sometimes, a smaller volume of business may not justify a full complement of experts and specialists in separate sub-functions. Combining sub-functions can be done without increasing operational risk or reducing management effectiveness. The key is to ensure objectives remain simple and there is separation of duties. No one who initiates transactions (the ‘salespeople’ and ‘traders’) should also be part of or manage a function that checks them (the ‘back office’). With the internal controls hard-coded into even cheaper treasury systems nowadays, even a smaller treasury can be well-organised.

Efficiency and effectiveness

All non-treasurers, those directly benefitting from or responsible for strategic treasuries, and those indirectly connected to them (people in related functions like finance and IT, suppliers, consulting firms, conference organisers, training firms, associations of corporate treasurers, academics and more) will note that these complex organisations have a much greater need to be efficient – doing the things right, faster, cheaper and with fewer errors – and also to be effective – doing the right things and stopping doing the wrong ones. Each of these types of non-treasurers has a role to play in helping make this possible, ensuring the people in these treasuries have the skills, the technology and the infrastructure – and this is crucial – all in the correct ratio. We will discuss this in the next and many of the following articles. The non-treasurers’ roles are that important!

Implementation

Creating a strategic treasury is feasible for an organisation like Acme Manufacturing, which has a multi-billion-dollar turnover. The remaining question is whether stakeholders believe the organisation can implement a major change like this successfully. It’s a valid question. We’ve covered the techniques needed to implement successfully, including how to cross the chasm in “Crossing the Chasm (Part II)”. Any organisation with $ 2 BN or more in revenue with complex cashflows wishing to implement this type of treasury can do so. It’s a matter of thinking it through carefully before starting to implement – of looking before leaping.

Close and next article

This article has covered strategic treasuries, particularly strategic solvency-managing treasuries. It has covered:

• What they are

• Their advantages

• Their costs and benefits

• Examples

• The importance of having a well-designed organisational structure

• The link between sophisticated risk and solvency management

• More

The behaviours of people as individuals and in groups have been a constantly recurring theme. Compared to technical, infrastructural, process and governance, this aspect is not covered nearly well enough in real life. What I have seen makes me think that this inattention to peoples’ behaviours explains the majority of frauds, actual and opportunity losses, and the strategic ineffectiveness of many treasuries. We will talk more about this in articles on tactical treasuries.

Armed with this knowledge, you, the thought leader of Acme Manufacturing, can now compile descriptions of strategic solvency-managing treasuries to allow your fellow key stakeholders to compare them to operational treasuries.

This in-depth comparison will be done in the following article. It will include, for the first time, an in-depth analysis of the systems and skills that a sophisticated treasury needs to be successful.

Next article: Sophistication in Solvency Management (Part III – Operational vs Strategic Treasuries)

Join our Treasury Community

Treasury Masterminds is a community of professionals working in treasury management or those interested in learning more about various topics related to Treasury management, including cash management, foreign exchange management, and payments. To register and connect with Treasury professionals, click [HERE] or fill out the form below to get more information.